Pricing doesn’t exist in a vacuum and is therefore not something you can tackle on its own.

Pricing doesn’t exist in a vacuum and is therefore not something you can tackle on its own.

Pricing is a function of marketing and determines, among other things, your market position. It also indicates – or is ideally derived from – the type of customer you want to do business with.

And of course in SaaS, pricing is tightly coupled to the product itself, which is different from other types of software and non-tech products where the price is decoupled from the product.

Which is why I can’t recall a time where a SaaS company came to me with a “pricing problem” and there wasn’t something else that was going on, too.

In fact, their “pricing problem” often had little to do with the actual “price” – the numbers – and more to do with pretty much everything else (chosen revenue model, customer segmentation, value proposition, marketing strategy, conversion optimization, etc.).

So, when those in an early-stage startup – or those bringing a new product to market within an existing company – ask me for help on pricing, I always say that you won’t get it perfect out of the gate, but you can get it as right as possible.

And then I give them a high-level pricing strategy framework, which I thought I’d document and share with you in this post.

Now I’ve written before about all of the inputs that need to go into developing your pricing model.

But this framework is different from pretty much everything I’ve talked about publicly (well, I’ve mentioned it before in passing) as it’s specific to early-stage startups and new products, so don’t assume you know what I’m going to say even if you’ve consumed everything I’ve published before.

It all started with this AHA! moment for me:

We Don’t Know what we Don’t Know

I had someone reach out to me recently and say “it was when you said in this post that no one knows what your startup pricing should be that I trusted you.”

Hmmm… so admitting that I don’t know something is good? Well then… I know very, very little!

Actually, when it comes to pricing and your startup, none of us know very much.

That’s because…

Everything will Change, Always

The very nature of a startup is that you don’t know what you don’t know, so developing a pricing strategy for launch that will also be relevant 6 months later (or maybe 6 hours later) is not going to happen and you shouldn’t try.

Instead, you should get something out the door, learn, iterate… OMG, MVP – Minimum Viable Pricing.

Please don’t ever say that, though. Thank you.

But really, you don’t know what you don’t know when you first start so keep it super-simple and increase the chances for learning.

In the early days…

Goldilocks Pricing isn’t Just Right

Most companies will attempt to go live with (at least) 3 retail pricing tiers, an Enterprise plan or two, annual discounts, and, for some odd reason, an overall strategy that LIMITS use.

Generally speaking, the reason for this is based on:

- Pretty much just making stuff up, or…

- Copying what other – usually completely unrelated – companies that sell to unrelated customers are doing, without knowing if that’s even working for them, let alone why it might work for you and your customers

Most of the time it’s a nice combination of both of those.

So, instead of wasting time and effort pulling things out of thin air (or somewhere else), acknowledge that you don’t know what you don’t know and go forward in a way that’s designed to intelligently fill those knowledge gaps.

That all said when it comes to pricing…

Only Learnings from Paying Customers Matter

Only intel from paying customers is valid when you’re trying to get intel on how to charge customers. Think about that for a minute.

What someone says they’ll pay or what they say your product is worth is irrelevant if they don’t follow that up with giving you money.

Rather, it’s much better to deeply understand the customer, their Desired Outcome, and the value of achieving that outcome.

For example, I’ve talked before about how Beta users aren’t actually customers and won’t give you the same intel (feedback, usage patterns, etc.) as customers that pay you something.

When it comes to pricing, at first…

Keep it Simple, Startup

So when I say keep it simple in the beginning, I’m talking about – if you can – going as far as offering unlimited access to everything (all features and functionality for unlimited users within their company) for a very specific cohort of early customers in exchange for a fee.

That first cohort can be as many customers as you like, but I suggest putting some bookends on how many you’ll let in and when they can sign-up.

Perhaps open your product up to 100 customers over a 30-day period, allowing you to ensure they all have a fairly similar experience (the numbers don’t matter here as much as the concept).

After you get 100 customers, you can turn off sign-ups for a bit – or not – but you should look at that group of customers as a specific cohort and monitor, measure, and learn from them on that basis going forward.

But first you need to…

Come up with a Price

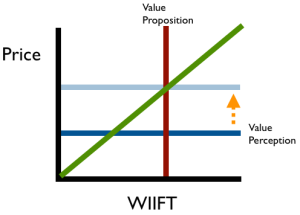

I’ve said it many times before; price should be an input on a spreadsheet, not a result from one.

There are financial implications to pricing, obviously, but if you need to charge $100/mo to achieve a 30% margin, but the market will only pay $50/mo for your product, all of the financial modeling to get to that price doesn’t matter.

So you need to come up with an initial price to start testing from, and that price needs to be derived from your understanding of the value the customer will derive from your product.

And this is where it gets really uncomfortable for those who don’t want to get to know (talk to) potential customers and who want quantifiable data points to build their startup from because it’s a lot more art than science at this point.

But hopefully, we can apply some scientific methods that move you from art to science.

Initial Pricing Inputs

“Umm, okay, are you actually going to tell us how to come up with a price, Lincoln?” you ask.

First, you need to figure out with whom you want to do business. This would be a great time to bust out the Ideal Customer Profile framework if you’ve not gone through it. Everything – Ev. Ery. Thing. – is easier and more effective when you’re focused on a very specific type of customer (especially in the early days).

From there you might look to the 10x rule – understanding the customer’s (theoretical) derived value and pricing at 10% of that – as well as all of the different inputs into an overall pricing strategy.

One of those critical inputs is how your customers buy; it doesn’t matter if you want to sell monthly via credit card if your customers don’t buy that way (yet).

You can also sanity check your initial pricing by looking to other vendors in the market to see if you’re way off base; though if you are, that doesn’t actually mean you’re wrong, it just means you may have to explain why you’re different.

Ultimately, the best thing you can do is…

Know Thy Customer (and Market)

In fact, if you come up with a pricing strategy that’s totally different than what the existing companies in the market use, it may be that you’re the only company in your product category to be right.

Unless you have direct intel otherwise, if you’re basing your pricing off of your understanding of the customer and their Desired Outcome, you’re closer to right than most companies. Guaranteed.

So you can also look to competitors, but do so to understand what customers may be used to / expecting vs. assuming your competitors got it right. You might also want to talk to some of their customers (start with those listed as advocates on their site) about their use of the product and how that jibes with the way the product is priced.

Also, look at how those competitive products are positioned… are they positioned lower or higher than where you’re going to come in? Figure that into your pricing.

You could look to adjacent products that sell to the same customers (and same individuals/departments within those companies) at the same position as yours (high-value vs. low-price leader).

So once you have your starting price, the fun begins as you…

Test your Prices

Pricing (like pretty much everything) is never a set-it-and-forget-it situation, and that’s never more so than in the beginning.

So, the first prospect you talk to on the phone or in person in the cohort will hear your pitch based on your initial value proposition hypothesis followed by the price you pulled out of the 10x rule.

After they convert (I’ll write something later about what happens if no one converts. Update: I never did), each subsequent prospect will be told a higher price (increase increments are up to you, but don’t be shy… +5% each time seems like a nice place to start) until you start to get some serious pushback; my friend Steli at Close.io says that until you get to 20% pushing back on pricing your prices are too low. I agree.

And yes, if you start out at say $100 and increase that by 5% each time, after 34 customers you’ll be at $500 (or if you start at $1000, you’ll be at $5000 by your 34th customer). That’s a big increase, but if you’re still not getting 20% pushback, keep raising the price until you do. Or you might run into that pushback at $105.

You just don’t know and you could end up leaving a ton of money on the table if you don’t test.

By testing the prices like this, you’ll start to get some idea of the price sensitivity vs. your value prop and you’ll have a much better place to start for the next cohort of customers.

I say it like that because you will learn use cases and the value realized by this cohort that will totally change your understanding of the value of your product to your customers.

Also, by testing prices behind the scenes with each prospect individually, you’ll avoid the type of pricing fiasco we’ve seen in the past where a company increased prices for new customers, didn’t tell existing customers about the change, and when the change was noticed on the website, existing customers thought they were going to have to pay the new, often much higher, price.

Fiasco-avoidance is a good goal, so remember when (or if) you end up publishing prices; if you do make a change, communicate that to your customers first (ahead of a public announcement) and assure them they’re grandfathered in and won’t have to pay the new, public price.

Value Prop Refactoring

Okay, so as you hit the 20% pushback threshold, you should probably refactor your value prop to ensure you’re hitting the right notes. You may be able to restart the price increases by changing your pitch.

All of this learning will very likely result in a massive price increase (assuming you position the product correctly to go along with that increase) with the next cohort.

And yes, this process will result in some customers being grandfathered in; while upgrading grandfathered early customers is something you’ll work through later, it’s not something to worry about right now.

No matter what, you will have to…

Talk to your Prospects

As part of keeping it simple, you’ll want to have a conversation with every prospect and pitch the price to them personally.

This is simple because it requires no design, engineering, programming, or other excuses not to do it.

Record those conversations (please conform to the laws that govern your jurisdiction) and get them transcribed so you can reflect on their questions, their pushback, and how you overcame the objections they raised.

I often hear from early-stage founders “no one converts through the self-service flow, but once I get on the phone with ’em, they convert like mad.”

This is usually because the self-service sign-up flow is all about the product, but when you talk to the customer you talk about them, use their language (mirroring), add some personality and excitement, or otherwise resonate with them on some level.

So get ’em on the phone, convert ’em like mad, learn from those conversations, and roll that “conversion magic” into the self-service sign-up flow (as well as other aspects of your sales and marketing).

Having those conversations recorded and taking note of what worked, what didn’t, what were common patterns and what were edge-cases will make optimizing your self-service sign-up process much easier and effective.

Once you’re converting customers at the top of the price you tested (20% are saying it’s too expensive), you’ll want to start looking for patterns that lead to…

Logical Price Segmentation

So, once you have a group of paying customers that have no limits on use, do everything you can to encourage wider and deeper use of the product. You should probably do this all the time, anyway, right?

This, by the way, is just one of the reasons for building your company around Customer Success from the very beginning.

Ultimately, we want the customers to use as many of the features as possible (so let them know all of the ways they can use it, schedule training calls, show them demos, make sure they’re clear on what they’re responsible for, bridge success gaps where they exist, etc.), explore as many use cases – both known and undiscovered – and get them to invite as many users from within their company as possible.

Why? We want to see how – unimpeded by limits on consumption, seats, etc. – real, paying customers actually use the product.

You’ll start to see – even with access to everything – that (roughly) 80% of your customers will only use 20% of the features (with possibly the same distribution among their users), and that’s just fine.

Of course you’ll want to validate this by ensuring that the 80% that are using 20% of the features are, in fact, achieving their Desired Outcome: they’re able to both achieve their Required Outcome and are doing so in the way they need or want (Appropriate Experience or AX).

You can only do that by talking to your customers, understanding their use cases, their experience, etc. Then you can start mapping those use cases and customer characteristics to the different pricing tiers.

Which means you’ll end up…

Mapping Pricing Tiers to Desired Outcome

I referred to Goldilocks Pricing in one of the headers above, and that’s the low, middle, and high price you so often see. It’s an age-old gimmick used to push people to the middle “just right” plan.

That means the high and low prices are decoys meant to trick the prospect into selecting the middle plan. You anchor them off the high and low plans so it makes the middle one seem like a good deal for what you get.

I could go on about why Goldilocks pricing is stupid – and maybe I will someday (update: I still haven’t) – but just consider that today we’re inundated with price gimmicks all day long across multiple devices, we’re busy and distracted, and we just don’t need to make more unnecessary decisions.

Every pricing plan you offer should have a story behind it; a use case, a type of customer, and a Desired Outcome.

In fact, when you start to tie pricing to Desired Outcome, you move into the revenue goodness that is real Value Pricing; selling outcomes rather than features and technology.

Assuming your customers’ Desired Outcome is being met, what you have with the 80% of customers using 20% of the features is essentially your entry-level pricing tier.

And the 20% using the other 80% of your features? Those are the folks using the “Advanced” or “Premium” tier and will likely be willing to pay a higher price.

Now, the Appropriate Experience portion of the Desired Outcome may differ across pricing tiers, meaning the higher-price tier may need to include better support, SLAs, etc.

Or not, perhaps that stuff is reserved for the Enterprise plan you wanted to launch with.

Regardless, this becomes…

The Path to Further Customer Segmentation

Within the 20% of customers using the other 80% of your product, you may also have another 20% using 80% of those features…. that may constitute an even higher-level tier.

Or you may find that the base 80% using 20% of the product can be further segmented themselves; perhaps bringing in a middle tier or carving out something at the low end or perhaps a free tier if you were to venture into the Freemium model (but probably don’t).

The more you can monitor use, talk to customers, understand Desired Outcomes and use cases, the better you’ll be able to position the pricing tiers for the appropriate audiences, and that will lead to…

Further Price Testing

After your first cohort of customers that have full, uninhibited access to your product, you’ll want to onboard another cohort, starting at the price where 20% of the prospect balked because it was too expensive.

After your first cohort of customers that have full, uninhibited access to your product, you’ll want to onboard another cohort, starting at the price where 20% of the prospect balked because it was too expensive.

But now you’ll have deep knowledge of your customers allowing you to start pitching the appropriate pricing plan for those in this next cohort, using appropriate language and value prop.

In fact, you’ll find that when you do this in a way that resonates with them, the price you originally started out with – that 20% said was too high – actually starts to seem really low!

As you continue your testing, you can funnel some customers to the self-service sign-up to see if the changes you’ve made help there. And if the changes don’t work, follow-up personally, bridge any gaps, overcome any objections, record the conversation, analyze it, and roll that back into all of your sales and marketing.

You’ll also (eventually) identify the…

Core Value Metric

During this process you’ll start to identify the core value metric for each pricing tier – should you end up moving away from unlimited access for a flat fee; and you likely will – that your pricing tiers will be based around.

I have to be clear here; you don’t have to move away from unlimited access, but many companies do for various reasons (board pressure, competitive pressure, profit, excessive costs to serve, etc.).

If you do move away from unlimited access per tier (after you’ve learned from your first few customer cohorts), you’ll want to find a metric that your customers find very valuable that doesn’t limit their use.

By its very design, per seat licensing limits the number of people that can use the product. That’s kinda the opposite of what we’re trying to do here, right?

So find a metric that doesn’t limit the number of users but, as they add more people, they need to buy more of that thing.

Example: Project Management software might be better priced on a per-project instead of per-user / seat basis. Pricing tiers could be segmented not on consumption or use (seats), but on functionality.

Then the Project Management software vendor could help the account owner understand other types of Projects they could manage with their software so they expand their own usage, then encourage the account owner to invite collaborators on those projects, and encourage those collaborators to spin up their own projects, and invite other collaborators on those projects. Viral.

Exponential, internal viral expansion is something that’s not possible – or incredibly difficult to achieve – when you have to make a buying decision just to bring another person into the product.

So, instead of putting your efforts into creating ways to limit use, put your effort into driving breadth and depth of use… so you can learn from that.

I hope this helps you…